God is the sovereign, eternal and omnipotent Creator, whose nature is manifested in three distinct but united persons: Father, Son and Holy Spirit. Throughout the biblical text, other names are used to refer to God, such as, eternal, creator, among others.

He is the Triune God, manifested in three distinct people, but united in essence and purpose: the Father, who reigns with sovereignty; the Son, who became incarnate for the redemption of humanity; and the Holy Spirit, who guides and sanctifies God’s people.

In the Protestant Christian tradition, the doctrine of sole scripture It establishes that the Bible is the supreme authority and sufficient to know the Lord, rejecting human traditions that place themselves above or equally with the inspired Word.

In this article we present a theological view of the Lord, based exclusively on the Scriptures.

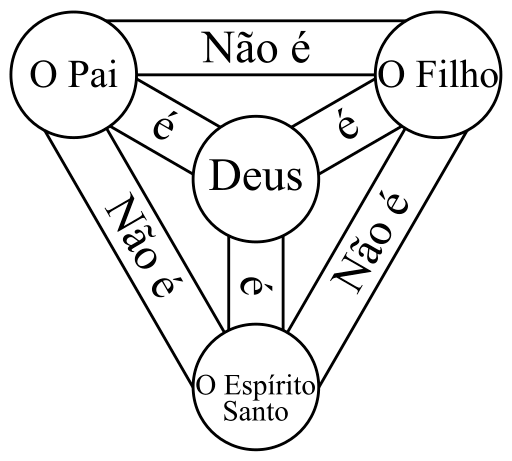

Trinity

The Doctrine of the Trinity It is the central foundation of the Christian faith, affirming that God is one in essence, but it exists eternally in three distinct persons: Father, Son and Holy Spirit.

This truth, although mysterious and beyond full human understanding, is revealed in the Scriptures and has been the object of theological reflection over the centuries.

It is essential that we approach the Trinity with reverence, recognizing its complexity and depth, while seeking to clarify its relevance to Christian faith and practice.

In this section we briefly present each of the three people of the Trinity.

God father

God the Father is the first person of the Trinity, the sovereign Creator of all things, whose authority and love permeate the biblical narrative. He is described as the ‘Father of Lights’ (Jas 1:17) and the origin of all creation (Genesis 1:1).

The Father is the source of the Trinity, the one who sends the Son and the Spirit to fulfill his redemptive purposes. His relationship with the Son and the Spirit is marked by a unity of essence and purpose, but distinct in function.

As Augustine of Hippo argues in of trinitate, the Father is the principle without principle, the one who generates the Son eternally without ever being subordinate in essence.[1]

In the economy of salvation, the Father is the one who plans and orders redemption. He is the architect of the salvific plan, sending his son into the world (John 3:16) and granting the Spirit to dwell in believers (John 14:26).

The paternity of God also extends to Christians, who are adopted as children through Christ (Rom. 8:15).

‘For God so loved the world that he gave his only begotten Son, that whoever believes in him should not perish, but have eternal life.

John 3:16 (NIV)

God son

The Son, Jesus Christ, is the second person of the Trinity, the eternal Word who became flesh (John 1:14). He is co-equal and coeternal with the Father, sharing the same divine but distinct essence in his person and mission.

The incarnation is the central mystery of the Son, where the divine nature is joined to human nature without confusion or separation, as defined in the Council of Chalcedon (451 AD).

As the author of Hebrews declares, the Son is ‘the radiance of the glory of the Lord and the exact expression of his being’ (Heb 1:3).

The Son is the radiance of the glory of God and the exact expression of his being, sustaining all things by his mighty Word. After having performed the cleansing of sins, he sat at the right hand of the majesty at the heights,

Hebrews 1:3 (NIV)

In the Trinity, the Son is eternally generated by the Father, a relationship that does not imply inferiority, but a functional distinction. He is the mediator between God and humanity (1 Tim 2:5), fulfilling the Father’s will through his life, death and resurrection.

Thomas Aquinas, in his Theological Summa, emphasizes that the Son is the word (logos) of the Father, through whom all things were made.[2]

God Holy Spirit

The Holy Spirit, the third person of the Trinity, is equally God, sharing the same divine essence of the Father and the Son. He is described as the ‘spirit of truth’ that proceeds from the Father (John 15:26) and is sent by the Son to guide, comfort and sanctify believers.

The Spirit is the agent of the divine presence in the life of the Church and of individuals, empowering them for the mission and transforming them in the image of Christ.

And all of us, who with the uncovered face contemplate the glory of the Lord, according to His image are being transformed with ever greater glory, which comes from the Lord, who is the Spirit.

2 Corinthians 3:18 (NIV)

The procession of the Holy Spirit, a theme debated in the history of the Church, was central to the schism between the West and the East, with the controversy of the filioque.

Theologians such as Gregory of Nazianzo produced works proving that the Spirit proceeds from the Father through the Son, maintaining the Trinitarian unity.[3]

The Spirit is the bond of love between the Father and the Son, and His work is essential in the application of salvation, regenerating hearts and inspiring the Scriptures.

“For the prophecy never came from the human will, but men spoke from God, impelled by the Holy Spirit.”

2 Peter 1:21 (NIV)

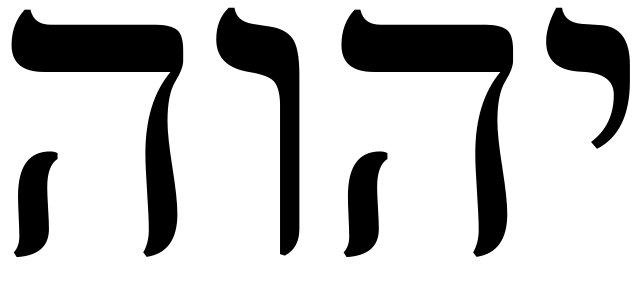

the name of god

In Christian theology, the name of God goes far beyond the function of a simple label, having a divine origin and being based on divine revelation.

The Bible often uses the name of God in the singular, as in Exodus 20:7 and Psalm 8:1, usually in a broad sense, without referring to a specific designation. However, these general references can unfold into special forms that express the different attributes of the Lord.

In the Old Testament, the personal name of the Lord is revealed as YHWH, commonly vocalized as ‘yahweh‘ or ‘Jehovah.’ In addition, titles such as El Elyon and he shaddai They are used to describe aspects of their nature.

When reading the Hebrew Bible aloud, the Jews replace the tetragrammaton (YHWH) with adonai, translated as kyrios in the Septuagint and the Greek New Testament. the abbreviated form jah, or yah, appears in the interjection ‘Hallelujah’, which means ‘Praise be Jah’, used by Christians to glorify the Lord.

In the New Testament, words like theos, God, and pater, father in Greek, are used to refer to the Lord, expanding the forms of divine designation.

Respect for the name of the Lord

Respect for the name of God is one of the Ten Commandments, which forbids its misuse and encourages its exaltation through godly deeds and praise. This principle is reflected in the first petition of the Lord’s Prayer: ‘Holded be thy name’, which expresses the desire to honor and glorify the divine name.

‘Thou shalt not take the name of the Lord thy God in vain, for the Lord will not let whoever takes his name unpunished.’

Exodus 20:7 (NIV)

Attributes and Nature of God

The discussion about the attributes and nature of God goes back to the first centuries of Christianity. In the 2nd century, Irineu de Lyon was one of the first to address this issue.

In against heresies, Irineu says: ‘His greatness lacks anything, but contains all things’.[4]

The divine attributes presented by Irenaeus were based on three main sources: the Scriptures, the then predominant mysticism and the popular piety[5]. Even today, many of these attributes are derived from both biblical statements. like the Lord’s prayer, which states ‘Our Father who you are in the heavens‘ (Mt 6:9).

The Eighteen Attributes of the Lord

In the 8th century, João Damasceno systematized eighteen divine attributes in his work an exact exposition of the Orthodox faith, organizing them into four groups: attributes related to time (such as eternity), space (such as infinity), matter and quality. thus defiing part of the Christian Orthodoxy.[6]

This classification remained influential in Christian theology for a few centuries, being reflected in several later theological works.

Thomas Aquinas and confessional traditions

In the 13th century, Thomas Aquinas prioritized a more concise list, including attributes such as simplicity, perfection, kindness, incomprehensibility, omnipresence, immutability, eternity and unity.[2]

Other ecclesiastical documents also addressed the issue, such as the Fourth Council of Lateran (1215), later reaffirmed by the Vatican I (1870), in addition to the Brief Westminster Catechism (1647).[7]

The Transcendence and Immanence of the Lord

Two attributes that highlight both the transcendence and the immanence of the Lord are particularly important.

Transcendence refers to the fact that the Lord is eternal, infinite and beyond the created world, not being subject to the limitations of creation.[8]

On the other hand, immanence recognizes that the Lord is actively involved in the world and in human affairs.[9]. Unlike pantheism, however, Christian theology claims that the Lord is not of the same substance as the created universe.[10]

Berkhof and the theology of communicable and incommunicable attributes

Louis Berkhof distinguished the attributes of the Lord among the communicable attributes and incommunicable attributes.

Communicable attributes have some correspondence in the human being, such as wisdom and goodness.

While the incommunicable attributes are those who belong only to the Lord and have no analogy in creatures, such as the immutability of the Lord.[11]

The Westminster’s Brief Catechism declares, ‘God is Spirit, infinite, eternal and unchanging in your being, wisdom, power, holiness, justice, goodness and truth.'[12]

Reformed Theology

Some Reformed theologians understand that this distinction between communicable and incommunicable attributes, although not formally explained in the confessions, is implicit in them.

The relationship between these attributes is such that the incommunicable qualify all others: for example, the Lord is infinitely wise, eternally just and immutably good.[13]

Donald MacLeod, in turn, questions these classifications, considering them artificial and without rigorous basis.[14]

It is widely accepted among theologians that the attributes of the Lord are not mere additional characteristics to their being, but rather essential qualities that eternally coexist with their essence. Changing any of these attributes would imply changing the divine essence itself.[11]

contemporary understandings

Theologian John Hick proposes that the list of God’s attributes must begin with the asseity or self-existence, from which other attributes such as eternity, immutability and infinity derive derive. Hick also points out that the Lord is the Creator (creatio ex nihilo), supportive, personal, loving, good and holy.[15]

In a similar way, Berkhof begins with self-existence and follows with attributes such as immutability, infinite that implies perfection and omnipresence, unity, omniscience, wisdom, truthfulness, love, grace, mercy, patience, holiness, righteousness and sovereignty.[11]

One of the first to philosophically affirm the infinity of the Creator was Gregory of Nissa. in your work against Eunomial, he argues that the goodness of the Lord is unlimited, and as this goodness is essential to his nature, he must also be considered infinite.[16]

God and humanity

The relationship between God and humanity is one of the central pillars of Christian theology. From the first verses of the Scriptures, the Lord is presented as the sovereign and personal Creator, who relates to his creation in an active and loving way.

The biblical narrative describes a progression that begins in creation, goes through the fall and culminates in the plan of redemption in Christ. This structure provides the framework for understanding human identity, the purpose of life and salvation.

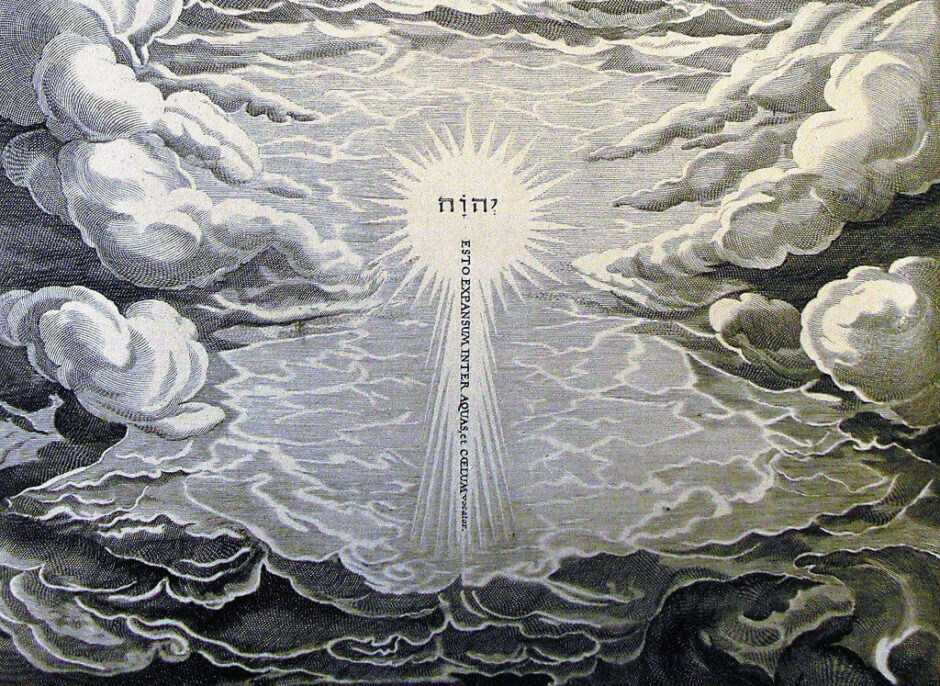

creation of the universe

Christian theology claims that God created the universe from nothingness by His mighty word (Gen 1:1-3; Heb 11:3). This creation was not the result of necessity or chance, but of a free and sovereign act of the Creator. He is distinct from his creation, but sustains it continually.

In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth.

It was the formless and empty land; darkness covered the face of abyss, and the Spirit of God moved on the face of the waters.

God said, ‘Let there be light,’ and there was light.

Genesis 1:1-3 (NIV)

According to Louis Berkhof, “creation is that work of God by which He brought into existence, from nothing, the world and everything that is in it, in a period of six days, and all very good”.[11]

Creation manifests the attributes of the Lord His power, wisdom and glory.[11]

In addition, the Doctrine of Creation It establishes that the world has purpose, order and value, challenging pantheistic or materialistic visions. As Alister McGrath states, ‘creation is both different from God and dependent on Him.'[14]

creation of humanity

The human being is considered “the crown of creation”. According to Genesis 1:26–27, the Lord created man and woman in His image and likeness (imago gave), giving them dignity, rationality, morality and relational capacity. This implies that the human being is called to reflect the character of the Lord and to exercise responsible dominion over creation.

[…]He blessed them, and said to them, ‘Be fertile and multiply! Fill and subjugate the earth!

Genesis 1:28 (NIV)

The imago gave It is not limited to functional attributes (such as reason), but involves a relational and spiritual vocation. John Stott points out that “being an image of God means being created to know God, obeying Him, loving and living in communion with Him.”[17]

Man’s Fall and Redemption Plan

The account of the fall in Genesis 3 narrates how the first human beings disobeyed the Lord, bringing sin, death and corruption to the world.

The fall not only affected individuals, but all creation. This rupture compromised the relationship between the Lord and humanity, establishing a condition of spiritual alienation.

Therefore, just as sin entered the world by a man, and by sin death, so also death came to all men, because all have sinned;

Romans 5:12 (NIV)

Augustine of Hippo, in his God’s city, argues that original sin is transmitted to all humanity and that only by divine grace can the human being be restored[18]. The fall, however, was not the end of the story.

In Genesis 3:15 the Lord promises a Redeemer indicating a plan of salvation from the beginning.

The plan of redemption takes place in Jesus Christ, the Incarnate Word, who lived without sin, died in replacement for the sinners and rose to grant eternal life (Rom. 6:23; Eph 2:8–9).

As J. I. Packer states, “Christ is the central point of the whole plan of the Lord the hermeneutic key of revelation and redemption”.[19]

Salvation is therefore the fruit of divine grace, offered to all who believe (John 3:16). This restoration not only reconciles the human being with the Lord, but also inaugurates a new creation, which will culminate in the renewal of all things.

Then I saw a new heaven and a new earth, for the first heaven and the first earth had passed; And the sea no longer existed.

I saw the holy city, the new Jerusalem, which descended from heaven from God, prepared as a bride adorned for her husband.

I heard a strong voice that came from the throne and said, ‘Now the tabernacle of God is with men, with whom he will live. They will be his peoples; God himself will be with them and will be his God.

He will wipe away every tear from his eyes. There will be no more death, no more sadness, no crying, no pain, for the old order has passed.’

He who was seated on the throne said, ‘I am making all things new!’ And he added, ‘Write this, for these words are true and trustworthy.’

Revelation 21:1-5 (NIV)

Other religions and their gods

Throughout the history of humanity, several civilizations have developed religious systems with multiple deities. These gods reflect the values, fears and hopes of their respective peoples.

From the mythological religions of antiquity to contemporary religions, the variety of beliefs reveals the universal search for the transcendent, but also reveals the limitation of man when trying to understand the divine by his own means.

The polytheistic religions

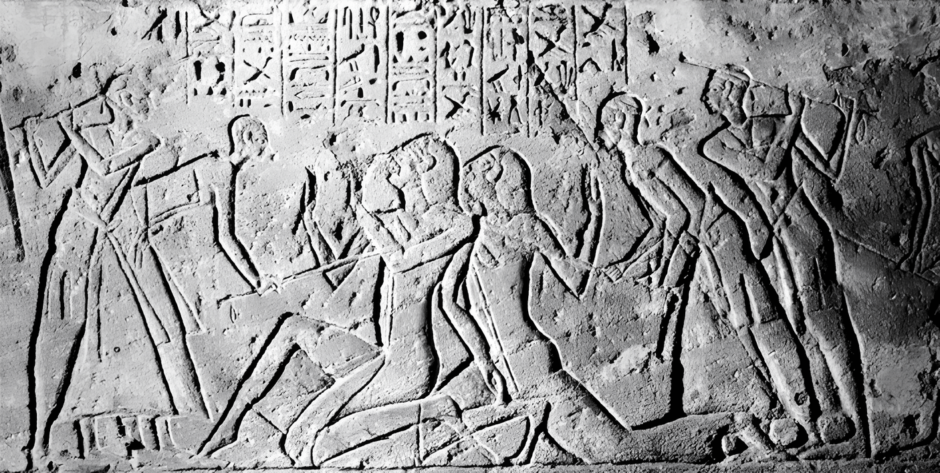

Civilizations such as the Egyptians, Greeks, Romans and Hindus present pantheons with multiple gods, each associated with specific aspects of life: love, war, harvest, death, etc. In ancient Egypt, for example, Horus, Isis and Osiris formed a central triad in religious worship.

The Greeks worshiped Zeus as the king of the gods, but shared their worship with Athena, Apollo, Aphrodite, among others.

These deities, however, had human characteristics were flawed, jealous, vindictive and even immoral. This shows that they were cultural projections, attempts to explain the world and the phenomena of nature. The apostle Paul alludes to this in Romans 1:22-23.

For since the creation of the world the invisible attributes of God, his eternal power and his divine nature, have been clearly seen, being understood through created things, so that such men are inexcusable;

Because, having known God, they did not glorify him as God, nor did they give him thanks, but his thoughts became futile and their foolish hearts were darkened.

By claiming to be wise, they became mad and exchanged the glory of the immortal God for images taken according to the likeness of the mortal man, as well as of birds, quadrupeds and reptiles.

Romans 1:20-23 (NIV)

The Eastern Religions

Religions such as Hinduism and Buddhism have different views on the divine.

Hinduism recognizes millions of gods and manifestations of Brahman, the supreme impersonal reality. Buddhism, on the other hand, does not affirm the existence of a Creator God, focusing on enlightenment and overcoming suffering through the Buddha’s path.

Despite their cultural and spiritual influence, these beliefs depart from the notion of a personal, holy, eternal and sovereign God, central characteristics of biblical revelation.

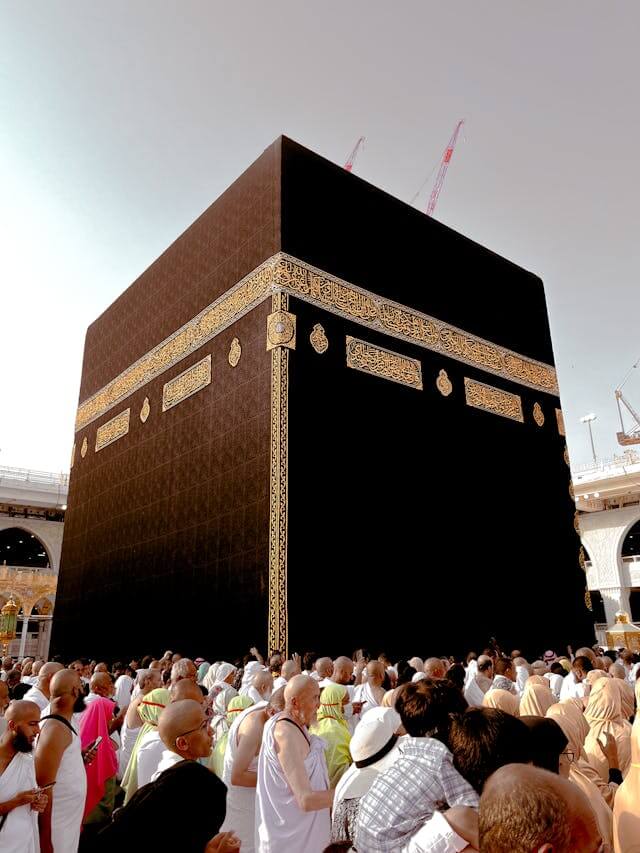

the Islam

Islam, although monotheistic, presents a conception of God (Allah) distinct from Christian revelation. The Quran describes Allah as sovereign and creator, but his relationship with human beings is far and marked by judgment.

There is not in Islam a concept of redemption by grace through a divine mediator.

The Christian God, the True God

Unlike pagan or impersonal gods, the God of the Bible is presented as unique, personal, eternal, creator and redeemer. He is not a human projection, but reveals himself to man through the Scriptures and, fully, in Jesus Christ.

a unique god

The Bible is clear in stating that there is only one true God:

Listen, O Israel: The Lord our God is the only Lord.

Deuteronomy 6:4 (NIV)

[…]Before me no God was formed, nor will there be any after me.

Isaiah 43:10 (NIV)

The Lord does not share His glory with idols or false gods. It does not depend on creation and exists by itself, being the foundation of all reality.

A gentleman who reveals himself

The Lord revealed himself progressively and sufficiently:

- In creation (Ps 19:1),

- in human consciousness (Rom. 2:14-15),

- in the Scriptures (2 Timothy 3:16),

- and fully, in Jesus Christ (Heb 1:1-3).

Christ is the image of the invisible God (Col 1:15) and through him we know the Father.

A God of Love and Justice

The Christian God is holy and just, but he is also loving and merciful. This tension is resolved on the cross of Christ, where divine justice was satisfied and love was fully demonstrated:

This consists of love: not that we have loved God, but in which He loved us and sent His Son as a propitiation for our sins.

1 John 4:10 (NIV)

No other religion presents a Lord who descends to man, takes on his pain, dies in his place and offers free forgiveness through faith.

learn more

[Vídeo] God’s Dreams. Gabriela Rocha.

[Vídeo] image of god. Bible Project.

[Vídeo] God. Bible Project.

common questions

In this section we present the main questions, with the answers, that people ask about the greatest character described in the Bible.

Quem criou Deus?

Deus não foi criado. Essa pergunta supõe que houve um outro criador antes de Deus. Entretanto, ao estudarmos as Escrituras somos forçados a aceitar que obrigatoriamente tinha que haver alguém que sempre existisse, que fosse eterno.

Deus é esse ser infinito e eterno, que existe além do tempo e além de sua Criação, ser ter sido criado. É algo um tanto difícil de compreendermos, pois somos finitos e limitados a esta Criação.

Como se definir Deus?

Deus é descrito como o ser supremo, onipotente, onipresente e onisciente, criador de todo o universo. Na Bíblia, é apresentado como um ser individual, com características semelhantes às de um ser humano, sendo o pai criador de tudo o que existe.

Sources

[1]Augustine of Hippo. of trinitate. Translated by Stephen McKenna. Washington, DC: The Catholic University of America Press, 1963.

[2]Aquinas, Thomas. Theological Summa. Translated by Fathers of the English Dominican Province. Westminster: Christian Classics, 1981.

[3]Gregory of Nazianzo. Theological Prayers. Translated by Charles Gordon Browne and James Edward Swallow. Crestwood: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1978.

[4]Irineu de Lyon. against heresies, Book IV, chap. 19.

[5]McGrath, Alister and. Historical Theology: An Introduction to the History of Christian Thought. São Paulo: Shedd, 2005.

[6]João Damasceno. an exact exposition of the Orthodox faith, Book I, chap. 8.

[7] Westminster Minor Catechism, question 4; Lateran Council IV (1215); Vatican I (1870).

[8]Barth, Karl. church dogmatics, vol. II.1. Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 1957.

[9]Pannenberg, Wolfhart. systematic theology. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1991.

[10]Plantinga, Alvin. God, Freedom and Evil. São Paulo: Vida Nova, 2012.

[11]Berkhof, Louis. systematic theology. São Paulo: Christian Culture, 2001.

[12] Westminster Minor Catechism, question 4.

[13]Frame, John M. the doctrine of god. Phillipsburg: P&R Publishing, 2002.

[14]MacLeod, Donald. behold your god. Fearn: Christian Focus Publications, 1995.

[15]Hick, John. An interpretation of religion: human responses to the transcendent. Yale University Press, 2004.

[16]Gregory of Nissa. against Eunomial, Book I.

[17]Stott, John. Basic Christianity. São Paulo: Abu Editora, 1999.

[18]Augustine. The City of God. Sao Paulo: Paulus, 1990.

[19]Packer, J. I. God’s knowledge. São Paulo: Christian Culture, 2004.

- Aroer – 10 de October de 2025

- Aijalom of Zebulun – 10 de October de 2025

- Aijalom of Dan – 10 de October de 2025